rida

The 2002 movie Frida, directed by Julie Taymor, with Salma Hayek, Alfred Molina, Antonio Banderas and Geoffrey Rush as main actresses and actors, depicts the private and professional life of the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, one of the most important Latin American painters. The film starts with the trip of Kahlo to her first solo exhibition in Mexico DF, the most wanted dream of this artist. The movie covers part of the teenager years and the whole adult life of the artist. During the trip, which was on a truck with the artist lying on her bed, she recapitulated her live, from when she was a teenager, a high school student, and was fascinated with the murals of the already famous Mexican painter Diego Rivera, to her life until this day of her trip to the Museum.

After a fatal automobile accident while in high school, Frida became almost paralyzed and had to be in bed for long time. Thus, to distract herself from boredom and pain she began to paint. Her initial paintings were mostly self-portraits and portraits of members of her family. She used to sign them and identify the sitter with an old XIX century tradition used in Mexico which consisted on adding a label on top or bottom of the painting. She started painting with a realistic style, almost inspired by the photographs of her father, Guillermo Kahlo.

She took the courage to bring her painting to be critiqued by Diego Rivera, one of the most famous Mexican muralists at the moment. Rivera was also a socialist leader and founder of the Socialist Party in Mexico. This moment was the beginning of a turbulent relationship between Frida and Diego involving friendship, camaraderie, passion, mutual admiration and love. Diego introduced Frida to his leftists-bourgeoisie, intellectual upper middle class group of friends that included international artists like the Italian photo journalist Tina Modotti and the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros. They were all members of the Communist Party, some of them Stalinist and some, including Rivera, Trotsky followers. They lived a bohemian life style, with openness to sex relationships and an admiration to the Russian Revolution socialistic goals; similar to the ongoing socio-cultural changes lived in Europe at the turn of the century.

Frida’s paintings continued evolving. Although her paintings had Diego’s influence regarding her vivid color palette and, her almost planar representation, the content of her paints was unique and very different from Rivera. When her health problems started escalating, her paintings shifted from her initial realism, into more personal depictions of either herself or representations of the Mexican people and their suffering. During her painful life, she developed a unique mix of expressionistic-surrealist style, mixed with the characteristic folk, art and culture of her beloved Mexican population. Most of her paintings are self-portraits and are like a visual auto-biography.

On the movie, Frida is depicted as bisexual. She had an affair with Tina Modotti and other women, not only in Mexico but also during her trips to the United States and France. Her marriage was always halted by the impulsive sex life of Rivera, which included Frida’s sister. Frida also had a share of lovers of both sexes, including the communist leader of the Russian Revolution Leon Trotsky. The movie plot adheres close enough to what I found in the literature about this controversial artist. It is clear that the self-centered Rivera, idolized by many, including Frida, was a very conflictive person and he was the source of the extreme emotions for Kahlo. The duality of Frida’s life is depicted on many of her paintings: as wife and a betrayed wife, as a bisexual person or as her Native Mexican-European mixed origin.

Frida’s life-style is close enough represented in the move. She is depicted wearing the attires the Native Mexican women wore, or cross dressing with some of the European traditions. Parallel, the movie emphasizes her love for the Mexican traditional food and the Mexican culture. Examples are her visits to the colorful “mercados,” her passion for Tequila and nocturne life on bars and parties and celebrating especial dates like the Day of the Dead and the decoration of her house, known as La Casa Azul.

Kahlo painted her pain and in some of the paintings, she made her pain universal. The writer Carlos Fuentes said about her paintings that “Frida represents the conquest of adversity… Frida Kahlo in that sense is a symbol of hope, of power, of empowerment, for a variety of sectors of our population who are undergoing adverse conditions” (2) It is interesting to compare this observation of Carlos Fuentes with Chadwick one about how Frida’s depiction of her own reality, reinventing herself and turning herself into magic object, also projected “male erotic desire” (Chadwick: 313). In a way although from very different points of view, both writers confirmed that through the self-observation and being observed, Frida explored her reality, her vulnerabilities, her dreams and pain, turning herself into a mythic symbol and an unknown persona, more desirable because of the unknown beyond her paintings.

Since Surrealism addressed the dreams and realities and the juxtaposition of both, some women artists found hard to take a direct approach to this movement. Like Frida, some women artist like Marie Cerminova (known as Toyen) used Surrealism to depict her political ideas about the war (Chadwick, 183). Surrealism still had a macho chauvinistic view of women, and saw women as muses, source of inspiration, with an erotic gaze. Many women artists turned towards the mirror to address the female body, representing the duality of seeing and being. (Chadwick: 114). As an example, Lenora Carrington, who was born in England, lived in Mexico and Simone de Beauvoir who addresses the feminine condition on her book published in 1949 The Second Sex. Other artists, like Dorothea Tanning, depicted sexuality using children and adolescent girls or the Spanish born artist Remedios Varo addressing, more existential and conflicting views of maternity and family (Chadwick: 115).

Surrealism and its transference as a movement to Latin America seems to be linked to the political turmoil Mexico was living during the first decades of the Twentieth Century. The influx of European artists and writers, probably related with the warmest of the Mexican people as well as that it was a more affordable option to live in created the perfect environment for creativity and this environment is painted in the movie.

It is hard to me to be completely objective about this film and hardest to separate what I knew about the artists before this film was created and Frida Kahlo’s depiction on the film. The first reason is related to the Mexican Revolution and the aftermath role of artists with the hope socialistic roots became established in Mexico. Frida, influenced by Diego Rivera, actively participated on the building of these socialistic ideals which were the foundation and the source of inspiration for many revolts in Latin America during the Twentieth Century being Cuba, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Salvador and Nicaragua the countries where were the strongest revolutions or revolts against militaristic regimes were more successful. It was also the inspiration for a smaller revolution in Costa Rica which effectively: abolished the army, set up a Universal Health Care System and in 1953, late, but early in Latin America, allowed women to vote during Presidential Elections.

Frida was a socialist since early youth, even before knowing Diego Rivera. She loved Mexico and its people and according to the records, she changed her date of birth date from July 6th, 1907 to July 7th, 1910, day of the beginning of the Mexican Revolution, not for vanity but because she felt intrinsic part of that important day in the history of Mexico (2). To me, the combination of her political activities with her surrealist, intimate, exploratory paintings of herself, were key elements to make Frida’s powerful body of work. I don’t see Frida’s paintings just as a depiction of her personal broken body or life. They are more universal, and in a way, she also turned the female body towards nature and with a Surrealistic approach, brought the relationships of women, nature and social power together.

The music of the movie is outstanding and I find exceptional the selection of singers: Lila Downs, Caetano Veloso and the legendary Chavela Vargas, who is believed, had a romantic relationship with Frida (see pictures of Chavela Vargas and Frida Kahlo on links 5 and 6.) The interpretations are close complement to the visual scenes and increase the emotion and depiction of Mexico throughout the whole film. Frida Kahlo loved the popular style of Mexican music “rancheras”, “boleros” and “corridos.” and the adaptations Julie Taymour and Elliot Gordenthal included on this film, to me add a lot of realism to what used to be parties and bar’s scenes in Mexico, very similar to many other Latin American countries.

This won’t be the last time I see this movie, since periodically, I go back to watch it, always ending up with a jealous feeling for the people who were born on these amazing years of awakening of this beloved Latin American, where macho-chauvinistic, patriarchal and catholic traditions, ruled together with militarist power and the rebellion started with of the intellectual, artists and middle class people. Perhaps with the eyes of a United States born person these are irrelevant issues, but Latin America is still flooded with social injustices, and the role of the Mexican artists of the period of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, is still of muses to many movements and emerging artists, writers, musicians, poets and the general public.

References

(1) http://www.fridakahlo.org/frida-kahlo-biography.jsp

(2) http://www.pbs.org/weta/fridakahlo/life/index_esp.html

(3) http://tierra.free-people.net/artes/pintura-frida-kahlo.php

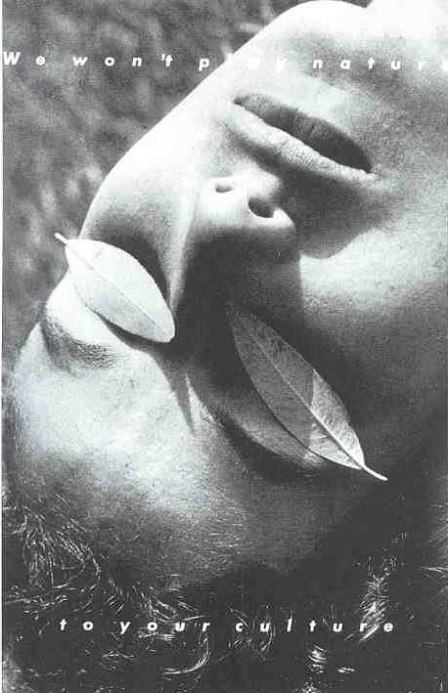

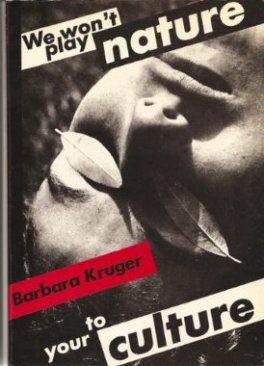

Barbara Kruger’s image untitled, known by the words included on the image “We won’t play nature to your culture” addresses the cultural perceptions of women in many ways.

Barbara Kruger’s image untitled, known by the words included on the image “We won’t play nature to your culture” addresses the cultural perceptions of women in many ways.